Nahavand, Avesta Art, Sweden, 2016

(In collaboration with Sirous Namazi)

Nahavand is a County in Iran located in one of the oldest regions in the country, with amazing landscapes, vibrant culture and ancient history.

The project Nahavand is a collaboration between artists Raha Rastifard and Sirous Namazi.

They both live and work in Stockholm but have their origins in Iran.

The project came out of their occasional discussions about this specific location, their homeland, and out of their desire to return.

In this project, the artists attempted to create a room and architecture inspired by Nahavand region in Iran, which, through its presence, indicates many lacking qualities in today's Iranian society.

An architecture which represents equality and transparency.

An architecture that would include and not exclude.

An architecture which harmonises with nature and the existing buildings in the surrounding.

A house conveying a message.

The artists aimed to experiment with these ideas and create an actual place where one can return, stay, meet, discuss, and reflect.

They aimed to immerse themselves and their audience in the idea about how and in what ways architecture can become a medium to transmute social discussions in an artistic way.

Nahavand is a work-in-progress project. What it has presented in its first exhibition was the first strike in a longer process.

This process continues to evolve and grow in scope.

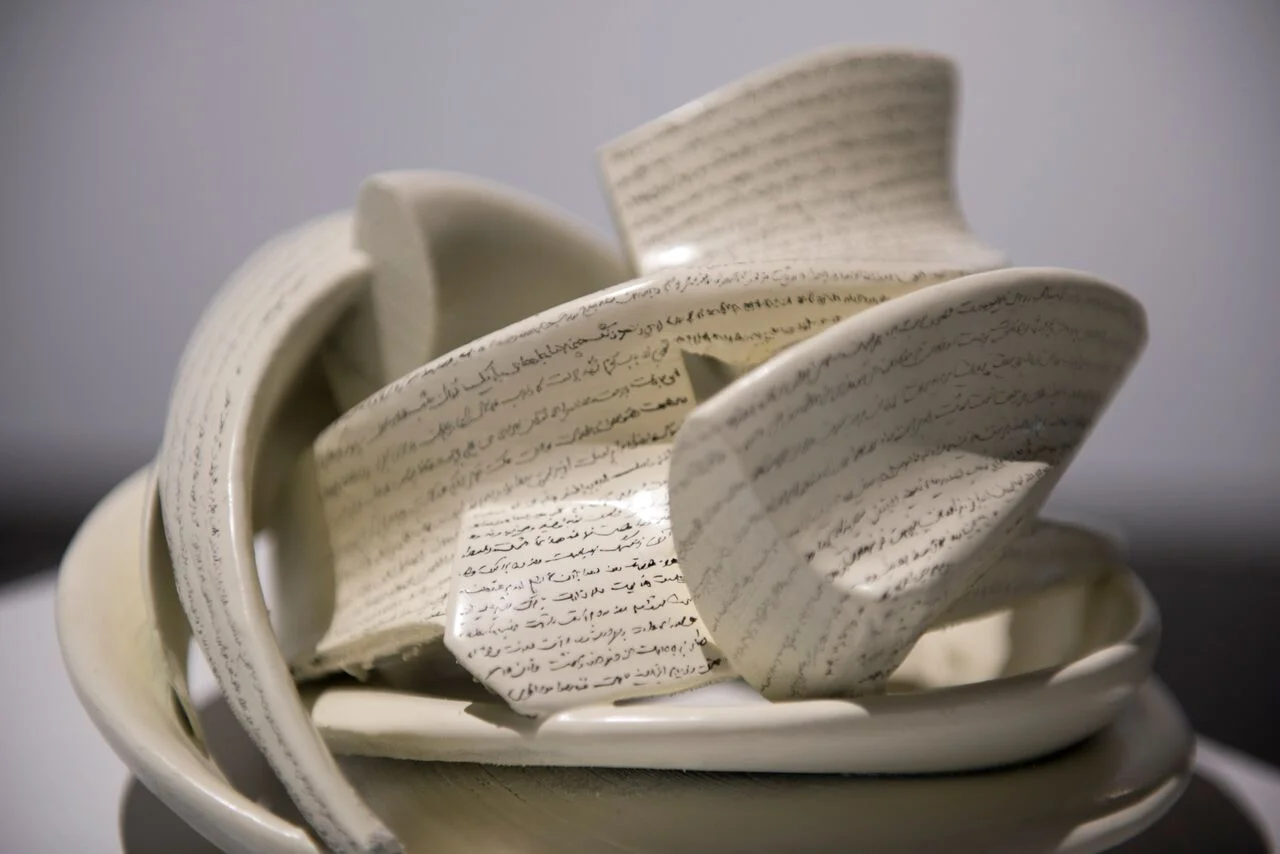

The photographs in the exhibition are Raha Rastifard’s two-week-long research trip to the region as well as Sirous’ three-dimensional architecture models and 3D renderings, on-going sketching for the final building.

The handwritten texts on models are adopted from Raha’s diary during the filed trip to the Nahavand region for this specific project.

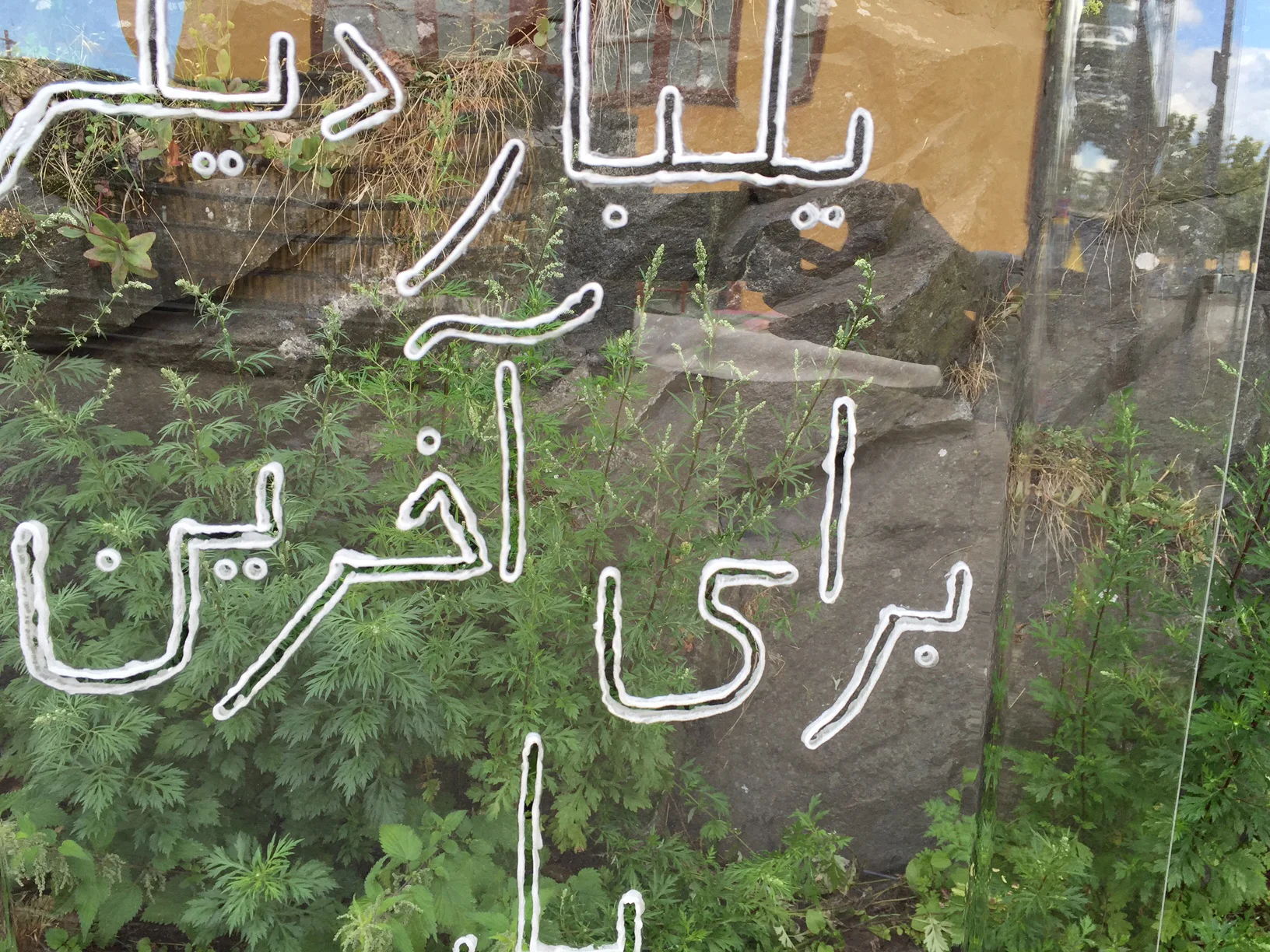

One more time, Stockholm Music & Arts 2016

''One More Time''.

Yes, one more time Maybe one more time for the last time I’m waiting as a refugee.

wait to get there; I look at another side!

The thematic is about escaping from places previously called home, of waiting and arriving at new homes. It is about the hardships of feeling as if you’re chased. disturbed while sleeping, and the dreams of new futures that can provide coexistence and security.

Tuba, 2007

In collaboration with Mehran Tizkar

“The photo project Tuba shows in eight light boxes the woman in Iran today in a society which is determined by tradition as a style and pattern of thought in every area of life. The ligree, stylized images re ect in the faces and postures a translucent power of tradition. The artists don‘t want to express a political opinion but represent the woman‘s view and idea of herself, abstracted in the medium of photography.

Tuba is the name of a huge, miraculous tree that grows nothing but jewels in Paradise - a symbol of strength and beauty. The photographs are presented in the exhibition rooms of the Islamic

art collection at the Pergamon Museum. The juxtaposition of ancient and contemporary art from the same cultural background in one exhibition space raises the viewer‘s awareness of many contrasts, such as the layers of variable and seemingly immutable values.”

Such describes the Iranian artist‘s couple its photographic series from 2006/2007, in which they seek to emotionally cope with their experiences in their home country Iran as well as during their emigration. The practice to use the diaphanous image as a reminder of veil, which simultaneously holds and disguises the vision, is familiar to us; it reminds us of the slides from our childhood

and of the illusory world of advertising photography. Here, this technique is being artfully used for processing memory in different layers and on different levels.

On the one hand, the “substance of memory” in the pictures consists of folk motifs such as the blindfold that is part of the women‘s traditional costume in the Gulf region of Bandar Abbas in the south of Iran. On the other, it pictures overwhelmingly large calligraphy and stark ornament that appear behind or next to the woman‘s guration and the blindfold and that originate from objects in the Museum of Islamic Art. It seems that the “museum aura” of these objects remind the artists of the origins of tradition and religion in Iran. We should not forget that this practice of connecting today‘s rites to history is not only carried out in the Orient. Today‘s museum visitors will not only be fascinated by the connection of the different levels of „beauty“ in both Creation and artistic production, but will also remember that artistic work is to be seen in the broader context of culture – contemporary critical art as well as commissioned art that has been produced for rulers and patrons in the past.

Text by Prof. Dr. Haase, former director of Museum of Islamic art, Pergamon Museum Berlin